Our

Legal Heritage

Bringing our past into the present

Since Singapore’s founding as a British colony in 1819, our legal system has been constantly evolving to meet the rapidly changing needs of the island nation. This evolution and the people behind our legal history are introduced here for researchers, students and the wider public.

Supreme Court

- Oral History

- Heritage Articles

- Publications

- Collaborations

- Events

Oral History

Our oral history project

From 2005, the Singapore Academy of Law began a systematic collection of memories and knowledge of Singapore’s legal history through recorded interviews with members of the legal profession and selected narrators who are familiar with key legal personalities. This project is carried out in partnership with the Oral History Centre (OHC) of the National Archives of Singapore.

Together with earlier work done by the OHC, hundreds of hours of oral history interviews have been recorded with more than 50 personalities across the strata of the legal community and the list continues to grow. These audio recordings, transcripts and synopsis of the interviews preserved for posterity are available to researchers from the NAS portal.

Over the years, we have also evolved from being a collector and depository of oral history recordings. As part of our efforts to create greater awareness and legal history, we have taken excerpts from these rich eye-witness accounts and shared them on our online blog as well as publications under Academy Publishing heritage series.

Our oral history programme focuses on two major themes:

Development of Singapore's Legal System

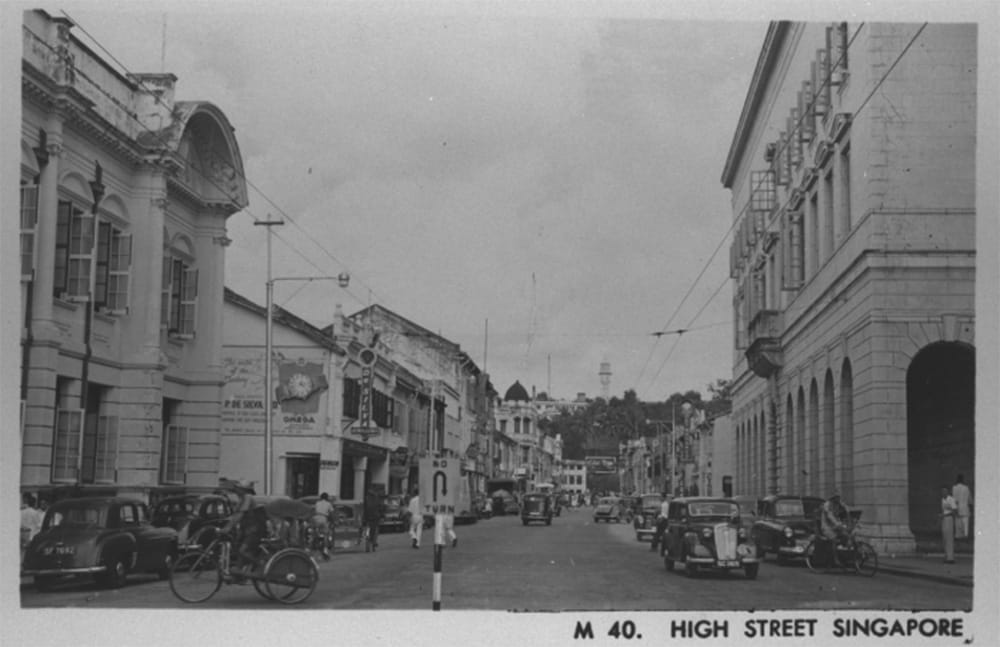

High Street in 1950 with the Public Works Department (PWD) building opposite the Supreme Court. The PWD building was later occupied by the Attorney-General Chambers. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Tracing the development of Singapore's legal system

This is an ongoing effort to capture personal accounts by legal personalities of their lives and careers and of the system in which they worked and their environs. Their stories trace the development of the legal profession from the pre-war years to Singapore’s independence from colonial rule and the localisation of the profession.

The audio recordings and transcripts of the interviews (subject to conditions stated by the interviewees) can be accessed through the NAS portal. Interviews marked with (*) were carried out by the NAS.

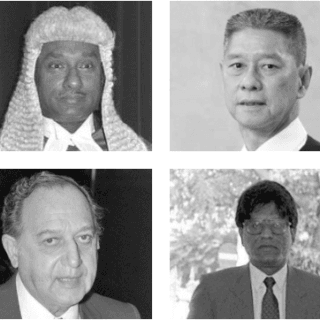

- Judges

- Legal Service Officers

- Practitioners

- Law Academics

- Others

- ABDUL Rahim Jalil (listen)

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Thian Yee Sze

Born on 9 April 1948, Abdul Rahim Jalil read law at the University of Singapore. He joined the Singapore Legal Service in 1971 and held various positions as State Counsel at the, Attorney-General Chambers and Magistrate, Coroner, District Judge and Deputy Registrar at the Subordinate Courts. He retired in 2010.

- CHOO Han Teck

Interviewed by Lim Jian Yi, Foo Kim Leng and Victoria Gomez

Born on 21 February 1954, Choo Han Teck is a judge of the Supreme Court. He read law at the University of Singapore and was called to the Bar in 1980. He entered private practice as a legal assistant in Murphy & Dunbar under the tutelage of Howard Cashin from 1980 – 1984. He then joined the National University of Singapore Law Faculty where he lectured for four years before returning to private practice in 1988. He was a partner at Allen & Gledhill from 1988 – 1992 before leaving to join a start-up – Helen Yeo & Partners, where he remained as a partner until he was appointed Judicial Commissioner in 1995. He was appointed Judge in January 2003. Choo was appointed President of the Military Court of Appeal of the Singapore Armed Forces on November 2004.

- Frederick Arthur CHUA* (listen)

Interviewed by Elisabeth Eber-Chan

Born in Singapore on 15 May 1913, Frederick Arthur Chua attended St Joseph’s Institution and Raffles Institution. He read law at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, and graduated in 1936. He was called to the Bar at Middle Temple in 1937. Upon his return to Singapore, he joined the Straits Settlements Civil Service and was appointed, in 1938, Assistant Official Assignee and Assistant Public Trustee in Singapore. He was transferred to Penang in 1940, and held various positions in Penang and Malacca before returning to Singapore in 1953 as District Judge and Magistrate. In February 1957, he was elevated to Puisne Judge of the Supreme Court, and served on the High Court Bench until 1992. Chua passed away on 24 January 1994, aged 81.

- LIEW Thiam Leng

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Mabel Seah

Born on 2 September 1949, Liew Thiam Leng read law at the University of Singapore. He joined the Singapore Legal Service in 1975 where he held various positions as State Counsel and Deputy Public Prosecutor in the Attorney-General Chambers and as Magistrate, State Coroner, District Judge and Deputy Registrar and Referee, Small Claims Tribunals at the Subordinate Courts. He was also Director of the Primary Dispute Resolution Centre. Liew was awarded the Public Administration Medal (Silver) in 2000.

- Francis George REMEDIOS

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Sellakumaran Sellamuthoo

Born on 19 August 1944. Francis Remedios read law at the University of Singapore. He joined the Singapore Legal Service in 1967 and held various positions as State Counsel and Deputy Public Prosecutor in the Attorney-General Chambers and as Magistrate, Registrar, District Judge and Coroner in the Subordinate Courts. Remedios also held appointments in the Requisition of Resources Compensation Board, Strata Titles Board, Income Tax Board of Review and Tribunal for Maintenance of Parents. He was awarded the Public Administration Medal (Gold) in 2000.

- Kasinather SAUNTHARARAJAH (K. S. Rajah) (listen)

Interviewed by Elisabeth Eber-Chan

Born in Penang on 3 March 1930, K S Rajah came to Singapore in 1950 and worked as a teacher studying law on a part-time basis at the University of Singapore. He graduated in 1963 and spent the next 22 years with the Singapore Legal Service heading the civil and criminal divisions of the Attorney-General Chambers. He also served as Director of the Singapore Legal Aid Bureau and head of the Official Assignee and Public Trustee’s Office. He retired from the Legal Service in 1985 and established the firm of B Rao & K S Rajah. In 1991, he was appointed a Judicial Commissioner of the Supreme Court of Singapore. He retired as a judge in 1995 and joined Harry Elias & Partners as a consultant. He was the first President of the Tribunal for the Maintenance of Parents in 1996. In 1997, he was among the first group of lawyers to be appointed Senior Counsel. He was conferred the Public Service Star 2002, and in 2008, he received the C C Tan Award, which recognises lawyers who display the highest ideals of the profession, from the Law Society of Singapore.

- Choor SINGH (listen)

Interviewed by Elisabeth Eber-Chan

Born in Korte, India, on 19th January 1911, Choor Singh completed his education, in 1929, at Raffles Institution. Thereafter, he worked as a solicitor’s clerk in Mallal & Namazie.

He was the founding member of the Singapore Khalsa Association, which was established in 1931. In 1934, he joined the Official Assignee’s chambers as a clerk. With the ending of the war, he registered for admission to London University in 1946; thereupon he joined Gray’s Inn. In 1949, he was the first Indian to be appointed Magistrate. Six years later, in 1955, he was called to the English Bar. In 1963, he was appointed Supreme Court Judge, where he served for 17 years. Singh retired in November 1980.

He passed away on 31st March 2009, aged 98.

- Thirugnana Sampanthar SINNATHURAY (T S Sinnathuray) (listen)

Interviewed by David Lee

Born on 2 September 1930, Mr Thirugnana Sampanthar Sinnathuray received his secondary education at Raffles Institution. He read law at University College, London and was called to the English Bar in 1954. On his admission to the Singapore Bar in 1955, he practised as an assistant in Oehlers & Choa. He joined Government service in 1956 and held various positions as District Judge, Deputy Registrar and Sheriff of Singapore, Crown Counsel and Deputy Public Prosecutor, Senior Crown Counsel and Registrar of the Supreme Court. He was appointed a High Court Judge from 1978 to 1997. For many years, he also served as President of the Singapore Cricket Club. Following his retirement from the Bench, he pursued his interest in numismatics, becoming the chairman and chief executive officer of Mavin International Pte. Ltd., an auction company specialising in rare coins and banknotes. Sinnathuray was conferred the Public Service Star in 1997.

- WEE Chong Jin* (listen)

Interviewed by Elizabeth Eber-Chan

Born in Georgetown, Penang, on 28 September 1917, Wee Chong Jin read law at St John’s College, Cambridge, and graduated in June 1938. He was awarded a McMahon Law Studentship and was called to the Bar at Middle Temple in November 1938. He returned to Penang and was admitted as an advocate & solicitor in 1940. He joined Allen & Gledhill and later moved on to Walters & Co. In August 1957, he was appointed Puisne Judge, and later Chief Justice of Singapore in 1963 until his retirement. Wee retired on 27 September 1990, aged 72. He passed away on 5 June 2005, aged 88.

- YONG Pung How

Interviewed by Thian Yee Sze, Foo Kim Leng and Serene Wee

Born in Kuala Lumpur on 11 April 1926, Yong Pung How read law at Downing College, Cambridge University and was called to the English Bar at Inner Temple in 1952. He returned to Malaya and practised law as a partner at his father’s law firm, Shook Lin & Bok. In 1953, he was appointed by the Singapore Government as arbitrator to resolve a dispute between the Government and a union. The union was represented by a young lawyer, Mr Lee Kuan Yew, who would go on to become Singapore’s Prime Minister in 1959.

Yong was admitted to the Singapore Bar in 1964. In 1969, he migrated to Singapore with his family and in1971, he switched from law to finance and formed Singapore International Merchant Bankers Limited (SIMBL) and the Malaysian International Merchant Bankers (MIMB) in Malaysia, serving as Chairman and Managing Director of both companies.

He joined Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation (OCBC) in 1976 ending up as its Chairman and Chief Executive. In 1982, he was seconded by the Singapore government to form and head the Government of Singapore Investment Corporation (GIC), and the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS). He was Chairman of Malaysia-Singapore Airlines between 1964 and 1969, and Deputy Chairman of Maybank between 1966 and 1972. He also served on the Securities Industry Council from 1972 to 1981; the Board of Commissioners of Currency from 1982 to 1989; and was Chairman of Singapore Broadcasting Corporation from 1985 to 1989. On 28 September 1990, Yong was appointed Chief Justice, replacing Wee Chong Jin.

He was credited with introducing sweeping reforms in the legal service, enhancing the quality and efficiency of Singapore’s judicial process and making the Singapore judiciary world-class. He was conferred the Distinguished Service Order in 1989 and the Order of Temasek (First Class) in 1999 in recognition of his outstanding contribution to the judicial system in Singapore. He was also awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws by the National University of Singapore Faculty of Law in 2001 and another honorary Doctor of Laws by the Singapore Management University (SMU) in recognition of his contribution to Singapore’s legal sector. The SMUSchool of Law was renamed the Yong Pung How School of Law from April 2021.

He retired as Chief Justice in April 2006 and was succeeded by Chan Sek Keong. Yong died on 9 January 2020, at age 93.

- Krishna Pillay Ram CHANDRA (K R Chandra) (listen)

Interviewed by Elisabeth Eber-Chan

Born in India on 2 November 1928, K R Chandra studied at the Johor English College at Johor Bahru before continuing his education in Singapore He graduated from the University of Malaya in Singapore in 1953 with a B A Hons (Economics), after which he joined the Administrative Service. In 1958, he studied law on a part-time course and obtained his LLB (Hons) from the University of Singapore in 1964. During his long career in the Civil Service, he served in various capacities including Acting Permanent Secretary (Prime Minister’s Office), Commissioner of Lands and Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Law, Ministry of Social Affairs and Ministry of Culture. He passed away on 20 April 1994.

- Tharumaratnam CHELLIAH* (listen)

Interviewed by Elisabeth Eber-Chan

Born in Jaffna, Sri Lanka, on 12 October 1921, Tharumaratnam Chelliah attended Raffles College, followed by the University of Malaya in Singapore where he earned his Bachelor of Arts (Hons) in 1956. Subsequently, he received his Bachelor of Laws from the University of Singapore in 1967. He joined the Administrative Service upon his graduation from Raffles College. In 1959, he was Assistant Secretary of the Ministry of Labour and Law, a position he served until 1962. In 1967, he was Deputy Secretary, Law Division of the Ministry of Law and National Development, a position he held until his retirement in 1976. Chelliah passed away on 17 January 2009, aged 88. - Abdul Wahab GHOWS (listen)

Interviewed by Elisabeth Eber-Chan

Born in Ipoh on 30 January 1921, Abdul Wahab Ghows attended Raffles College. He was called to the Bar at Middle Temple in 1952. Upon his return to Singapore, he commenced his legal career as a traffic Magistrate. In 1954, he was appointed Assistant Official Assignee. Four years later, he was Deputy Public Prosecutor and Crown Counsel, and then appointed Solicitor-General in 1971, aged 50. In 1980, he was elevated to the High Court Bench where he served for five years. Ghows retired in October 1986, aged 65, after 34 years in legal service and the Judiciary. He passed away on 27 January 1997, aged 76.

- Graham Starforth HILL

Interviewed by Eleanor Wong and Victoria Gomez

Born in Oxford on 22 June 1927, Graham Starforth Hill read law at St John’s College, Oxford. Working for the Colonial Legal Service, he came to Singapore in 1953, where he was Crown Counsel until 1956. The following year, he joined Rodyk & Davidson where he rose to senior partner. He remained at the firm until 1976. He was the President of the Law Society of Singapore for four terms from 1969 to 1972. He left Singapore in 1976 and has worked in the UK and Italy. Hill retired in May 1994 and now resides in Hampshire, UK.

- Joshua Benjamin JEYARETNAM (J B Jeyaretnam) (listen)

Interviewed by Elisabeth Eber-Chan

Born in Jaffna, Sri Lanka, on 5 January 1926, Joshua Benjamin Jeyaretnam attended the Government English School in Muar, Johor Bahru, before the war and subsequently continued his education in Singapore at St Andrew’s School from 1945 to 1946. He read law at University College London from 1948 to 1951. His legal career began as Magistrate, then Judge of the District Courts from 1952 to 1957. He served as Registrar of the Supreme Court from 1961 to 1963, when he left for private practice. He made his entry into the political arena in 1971 and was elected Member of Parliament of Anson Constituency in 1981 and 1984. Jeyaretnam passed away on 30 September 2008, aged 82.

- KOH Eng Tian (listen)

Interviewed by David Lee

Koh Eng Tian was the first Solicitor-General of Singapore from 1981 -1991. Born on 20 January 1938, he was among the first batch of students to graduate from the University of Malaya Department of Law in 1961. He joined the Legal Service and worked as a legal officer in the Inland Revenue Department and thereafter at the Attorney-General Chambers under AG Tan Boon Teik. He was responsible for drafting many of the new Bills that were passed after Singapore gained independence in 1965. He also helped to draft the IRAS Act. He was one of the first two Senior Counsel appointed in Singapore in 1989 when high ranking legal officers such as the Attorney-General and Solicitor-General, are automatically appointed as Senior Counsel upon holding office.

- TAN Boon Chiang (listen)

Interviewed by David Lee, Lim Jian Yi and Foo Kim Leng

Born on 4 June 1923, Tan Boon Chiang was the President of the Industrial Arbitration Court from 1984 to 1988. He received his education at Anglo-Chinese Secondary School and Raffles College. He then read law at University College, London and was called to the English Bar in 1954 and the Singapore Bar in 1959. He spent more than 30 years in the Legal Service where he also held positions as Crown Counsel and Deputy Public Prosecutor before moving on to his post at the Industrial Arbitration Court. He served as President of the Singapore Anglo-Chinese School Old Boys Association and was a member of the ACS Board of Governors. He passed away on 28 December 2015, aged 92.

- TAN Lian Ker (listen)

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Mabel Seah

Born in Segamat, Johor, Malaysia, on 28 May 1929, Tan Lian Ker started his foray into the legal service as a court interpreter in 1951. In 1953, he was certified an interpreter of the Criminal District & Magistrates’ Courts. Whilst working, he also read law part-time at the University of Singapore and graduated in 1964. Thereupon he entered government service. In 1967, he was appointed State Counsel, Attorney-General’s Chambers. He was appointed District Judge in the Civil District Courts in 1970. He was District Judge of the Subordinate Courts for ten years from 1974 until 1984. Tan was awarded the Public Service Star award in 2010.

- TAN Wee Kian (listen)

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng

Born in Singapore on 21 March 1932, Tan Wee Kian attended Raffles Institution up to 1952. In September that year, he enrolled as a student at Gray’s Inn and was called to the English Bar in February 1957. Upon his return to Singapore, he joined the Legal Service in 1958 and served in various capacities as Deputy Public Prosecutor, Crown Counsel, Assistant Official Assignee and Public Trustee, Magistrate, District Judge, Deputy Registrar of the High Court, Sheriff, Acting Registrar of the High Court and Registrar of Titles and Deeds. Tan was appointed Registrar of the Supreme Court in 1969 and held that post until 1977.

- Subhas ANANDAN (listen)

Interviewed by Balasakher Shunmugan

Born in Kerala, India on 25 December 1947, Subhas Anandan attended primary and secondary school in the naval base where his father worked as a clerk in the British Royal Navy. He obtained his law degree from the National University of Singapore in 1970 and did his pupillage under Chan Sek Keong at Shook Lin & Bok. After he was called to the Bar in 1971, Anandan started his own practice sharing the premises with his friend, M. P. D. Nair. Following Nair’s death, became the managing partner of M. P. D. Nair & Co. In 2000, Anandan closed the firm and joined Harry Elias Partnership as a consultant to help build up its criminal practice. In 2007, he joined KhattarWong to head the firm’s criminal practice. Anandan started the Association of Criminal Lawyers of Singapore in 2002, with the goal of raising the number of criminal lawyers in the country. In 2011, Anandan, he founded RHTLaw TaylorWessing and remained one of its senior partners until his death on 7 January 2015.

- Howard Edmund CASHIN (listen)

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Thian Yee Sze

Born in Singapore on 29 November 1920, Howard Cashin read law at University College Oxford in 1939. He was called to the Bar at Inner Temple, and then to the Singapore Bar on 14 September 1951. He practised at Rodyk & Davidson but left in 1960 to join Murphy & Dunbar. He took over as senior partner upon Murphy’s departure in 1973. This marked the beginning of his career as the Bar’s leading criminal lawyer. He retired from Murphy & Dunbar in 1988, remaining as consultant. He was a keen sportsman and served as President of Singapore Rugby Union from 1977-1986. Cashin passed away on 5 September 2009, aged 89.

- Harry ELIAS SC (listen)

Interviewed by Elisabeth Eber-Chan

Born on in the Jewish quarter in Singapore on 4 May 1937, Harry Elias studied at St Andrew’s School where he was active in rugby, hockey and debating. He taught in a primary school in Singapore for two years before travelling to London to read law. There, he pursued an external degree while teaching at the same time to supplement his income. He graduated in 1963 and started work at Shearn Delamore & Company in Kuala Lumpuer in 1965. He joined Drew & Napier in Singapore in 1970 and became an administrative partner in 1979. In 1988, he started his own practice, Harry Elias & Partners. He was President of the Law Society of Singapore between 1984 and 1986. He co-founded the Criminal Legal Aid scheme (CLAS) in 1985 to provide legal aid to those facing criminal charges but who could not afford lawyers. He was among the first appointed Senior Counsel in 1997 when the Senior Counsel system was introduced in Singapore. He passed away on 27 August 2020, aged 83. - Alec Crowther FERGUSSON*

Interviewed by Jason Lim

Born in Dewsbury, Yorkshire, on 14 March 1934, Alec Fergusson read law at Leeds University. His father was a solicitor who had influenced him into becoming a solicitor. He did national service in England between 1956 and 1958. He was interviewed in London for a position in Drew & Napier Singapore which he accepted. He arrived in Singapore in 1958 and started out as a legal assistant. He became partner in 1964 and was there until the end of 1983. The following year, he set up his own firm in Singapore. Fergusson passed away on 26th March 2000, aged 66.

- GIAM Chin Toon SC

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Victoria Gomez

Born on 11 October 1942, Giam Chin Toon read law at the University of Singapore. He joined the Singapore Legal Service in 1967 and was a Magistrate when he left for private practice in 1970. Giam practised at Ong Swee Keng & Company before joining Wee Swee Teow & Co in 1973 where he is today a senior partner. A former President Law Society of Singapore, Giam played a key role in developing and growing the Society’s Criminal Legal Aid Scheme where he served as its Chairman. He was also formerly Chairman of the Law Society’s Inquiry Panel. He was among the first batch of Senior Counsel appointed in 1997 and was conferred the CC Tan Award by the Law Society in 2006. He is Singapore’s roving Ambassador to Peru and non-resident High Commissioner to Ghana.

- Joseph GRIMBERG SC (listen)

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Daniel Chew

Born in Singapore on 8 April 1933, Joseph Grimberg read law at Cambridge and was admitted to the Bar in October 1957. He joined Drew & Napier as a legal assistant and was the first local senior partner of Drew & Napier at the tender age of 33. After 20 years as a senior partner, he was appointed a Judicial Commissioner in November 1987, aged 54. He served in that capacity until January 1990, after which he was among the first batch of lawyers in Singapore to be conferred the title of Senior Counsel in 1997. For his personal integrity, honesty and outstanding contributions to the law community in Singapore, Grimberg was conferred the CC Tan Award by the Singapore Law Society in 2007. A keen hockey and cricket player, Grimberg also served as a former president of the Singapore Cricket Association. He passed away on 17 August 2017, aged 84.

- Clive Boon Howe HENG (listen)

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng

Born on 15 September 1953, Clive B H Heng studied mostly in the UK and graduated from London University in 1975. He was called to the English Bar in London in 1976. Upon his return to Singapore, he did his pupillage under Howard Cashin at Murphy & Dunbar and worked as a legal assistant in the firm from 1980 to 1990. He then left practice to work at Wilmer Holdings Pte Ltd where he was Managing Director until his retirement. Heng passed away on 1 May 2021 at the age of 68.

- Kenneth HILBORNE (listen)

Interviewed by Eleanor Wong

Born on 29 April 1919, Kenneth Hilborne was a Londoner and qualified solicitor in England who was admitted to the Singapore Bar on 5 July 1948. He was chiefly a conveyancer, and practised in Hilborne & Murphy until it was closed in 1955. He then formed Hilborne & Co and was later joined by Chung Kok Soon. Shortly after this, he retired and left Singapore. Hilborne passed away in September 2008.

- Michael HWANG SC

Interviewed by Eleanor Wong

Born on 14 November 1943, Michael Hwang SC read law at Oxford University. After completing his legal education, he took up a teaching appointment at the Faculty of Law at the University of Sydney. He was called to the Singapore Bar in 1968 when he joined Allen & Gledhill and retired from the firm in 2002. In 1991 he was appointed a Judicial Commissioner of the Supreme Court of Singapore and returned to private practice in 1993. e was among the first batch of lawyers to be conferred the title of Senior Counsel in 1997. He currently practises at a barrister and arbitrator. He has held office in various international arbitration institutions, having been involved in many arbitrations and mediations involving countries in Asia Pacific and beyond.

- Sat Pal KHATTAR (listen)

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Sellakumaran Sellamuthoo

Born in Bhera, in present-day Pakistan on 22 November 1942, Sat Pal Khattar read law at the University of Singapore. After graduation in 1966, he joined the Singapore Legal Service as a Deputy Public Prosecutor and State Counsel at the Attorney-General’s Chambers. This was followed by a shift to the Inland Revenue Office (IRO) as a legal officer. He resigned from the IRO in 1974 to start his own firm Sat Pal Khattar Company.

It was later renamed Khattar Wong & Partners when property lawyer, David Wong joined the firm. Khattar retired from law practice in 2000 and established Khattar Holding, a private investment firm. Since the early 1990s, he has been investing in India, and this experience has helped him promote and support bilateral trade and investments between Singapore and India. He has served on many civic bodies in Singapore in various capacities and has been honoured at the May Day Awards on several occasions. He was the first resident in Singapore to receive the Padma Shri Award from the Indian government.

- Michael KHOO SC

Interviewed by Eleanor Wong, Foo Kim Leng, Victoria Gomez and Ashutosh Ravikrishnan

Born on 7 November 1943, Michael Khoo SC studied at St Joseph’s Institution and completed his law studies at the University of Singapore in 1967. He joined the Singapore Legal Service and served in various judicial positions including that of Senior District Judge and Registrar of the Supreme Court as well as Senior State Counsel and Deputy Public Prosecutor in the Attorney General’s Chambers in a public service career spanning 20 years, before entering private legal practice in 1987. He was among the first appointed Senior Counsel in 1997 when the Senior Counsel system was introduced in Singapore. He is currently the founder and precedent partner of Michael Khoo & Partners.

- Glenn Knight (listen)

Interviewed by Eleanor Wong

Born on 13 November 1944, Glenn Knight studied at Anglo Chinese School and completed his law studies at the University of Singapore in 1970. After graduation, he joined the Singapore Legal Service and served in various positions as Deputy Public Prosecutor and State Counsel in the Attorney-General Chambers. He was the first Director of the Commercial Affairs Department (CAD) when it was founded in 1984. He lost the post in 1991 after being convicted in a much-publicised trial. Following his first conviction, Glenn Knight was disbarred from legal practice in 1994. Four years later, he was convicted again for misappropriating CAD funds during his stint as director. It took more than a decade before his application to be reinstated was granted in 2007. He currently practices in a small law firm.

- LIM Chor Pee* (listen)

Born in Penang, Malaysia on 18 June 1936, Lim Chor Pee attended Penang Free School. In 1955, he went to Cambridge where he read law at St John’s College. He was called to the English Bar at Inner Temple in 1959 and was admitted to the Malayan Bar in Singapore in 1962. He joined the Singapore Legal Service from 1960 -1964 where he served in various capacities including Crown Counsel and Deputy Public Prosecutor in the Attorney-General’s Chambers, District Judge and Magistrate and legal officer in the Legal Aid Bureau and the Economic Development Board.

In 1964, Lim and his colleague Khoo Hin Hiong who was then a Magistrate at the District Court, set up a two-man law firm, Chor Pee & Hin Hiong on Robinson Road.. After this company was dissolved, he founded Chor Pee and Company, which later became Chor Pee & Partners. In the early 1990s, Chor Pee & Partners was among the first handful of foreign law firms that were granted licences to open offices in Vietnam, at a time when few other local firms had branched out into the region. The company was dissolved upon his death.

Apart from his career in the law, Lim was one of the prime movers of Singapore’s English-language theatre. He was among the first batch of playwrights in the 1960s. He founded the Experimental Theatre Club to create “Malayan theatre” and to encourage local playwrights by staging their plays in a scene dominated by expatriates. He produced many plays including “Mimi Fan” and “A White Rose at Midnight” which he wrote. He passed away on 5 December 2006.

- David MARSHALL* (listen)

Interviewed by Lily Tan

Born in Singapore on 12 March 1908, David Marshall attended St Joseph’s Institution and Raffles Institution. He was called to the English Bar at Middle Temple in 1937. In 1938, he was called to the Singapore Bar. He worked at Aitken & Ong Siang, rapidly building a reputation for himself in criminal litigation. In 1940, he joined Allen & Gledhill and, after the war, was made its first Asian partner in 1949, aged 41. He resigned soon after, and joined Battenberg & Talma in January 1950. He entered the political arena and became Chief Minister in 1955 for 14 months. He served as ambassador for nearly 12 years to France, then Portugal, Spain and Switzerland from 1978. Marshall passed away on 12 December 1995, aged 87.

- T P B MENON (listen)

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng

Born on 10 March 1937, Mr TPB Menon was among the pioneer batch of 22 law students who graduated from Singapore’s first law faculty in 1961. Mr Menon was senior partner of Oehlers & Choa before it merged with Wee Swee Teow LLP in 1989. He was senior partner of Wee Swee Teow LLP from 1989 to 2000 and is now a Consultant at the firm. He was President of Law Society from 1980-83 and was awarded the Society’s highest honour – the CC Tan Award in 2004.

- Chelva Retnam RAJAH SC

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Victoria Gomez

Born on 3 November 1948, Chelva Rajah read law at Lincoln College, Oxford University from 1967 till 1970. He was called to the English Bar at Middle Temple in 1970 and has practised at Tan Rajah & Cheah since being called to the Singapore Bar in 1972.

- Gopalan RAMAN (G Raman) (listen)

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng

Born in 1938 in north Perak, Raman worked as a court interpreter in the Singapore courts from 1956 to 1966 during which he studied for his A Levels and an external law degree. He re-started his law practice in 1978 and became a leading authority on probate, wills and trusts. He was awarded the Singapore Law Society’s CC Tan award in 2014 for exemplifying the virtues of “honesty, fair play and personal integrity”. G Raman passed away at the age of 82 on 9 December 2020.

- Vengadasalam RAMAKRISHNAN (listen)

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Sellakumaran Sellamuthoo

- Pathmanaban SELVADURAI* (listen)

- Anamah TAN

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Victoria Gomez

- Phyllis TAN

Interviewed by Joseph Yeo

Born in Singapore on 15 June 1933, Phyllis Tan attended Raffles Girls’ School. She was called to the Bar at Middle Temple in 1955 and was admitted to the Singapore Bar in May 1956. She began her career as a legal assistant in Eber & Tan. Upon Mr Eber’s death, the firm was called Tan & Tan, where she practised with her father. She was a part-time lecturer at the University of Singapore from 1973 to 1977. She was the first female President of the Law Society of Singapore in 1979. Tan retired in 1998.

- TANG See Chim

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Sellakumaran Sellamuthoo

- WONG Meng Meng SC

Interviewed by Eleanor Wong

Born on 5 August 1948, Wong Meng Meng read law at the University of Singapore and was admitted to the Singapore Bar in 1972. He joined private practice working at Braddell Brothers, Lee & Lee and Shook Lin & Bok. He founded WongPartnership in 1992. He retired from the partnership in 2006 and remains with the firm as Founder-Consultant. In 1997, he was among the first group of lawyers to be appointed Senior Counsel. He was President of the Law Society from 2010 -2012.

- Helen YEO

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Victoria Gomez

Born on 18 August 1950, Helen Yeo read law at the University of Singapore. She joined Chor Pee and Hin Hiong after graduating in 1974. The firm was later renamed Chor Pee and & Company. In 1992, Yeo and a few partners from the firm quit to set up Helen Yeo & Partners. In 2002, Helen Yeo & Partners merged with Rodyk & Davidson and Yeo continued as Managing Partner of Rodyk until her retirement in 2010.

- Peter ELLINGER (listen)

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Victoria Gomez

- Tommy KOH* (listen)

Interviewed by Teo Kian Giap

- Lionel Astor SHERIDAN

Interviewed by Eleanor Wong

- Myint SOE (listen)

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Lim JIan Yi

- TAN Sook Yee (listen)

Interviewed by George Wei, Margaret Chew and Foo Kim Leng

- THIO Su Mien

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng

- Umayal BALAKRISHNAN

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Ashutosh Ravikrishnan

- Nellie BONSALL (Wee Chooi Geok) (listen)

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng

Wee Chooi Geok was born on 18 July 1911 in Penang. Her brother, Wee Chong Jin was the first Asian to be appointment the position of a judge at the Supreme Court of Singapore, and subsequently Chief Justice of Singapore. This is a supplementary interview on her recollections of former CJ Wee. - Gerard FERNANDEZ (listen)

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng, Victoria Gomez and Ashutosh Ravikrishnan

- Ahmad Hashim bin SALIM

- Teekesh TIWARI

- Ann Elizabeth WEE (listen)

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng

Ann Elizabeth Wee was born in England on 19 August 1926. She moved to Singapore when she married lawyer Harry Lee Wee in 1950. For the next four decades, Wee served in various capacities of social work in Singapore. She passed away on 11 December 2019 at age 93. This is a supplementary interview on her recollections of her husband Harry Lee Wee.

- Serene WEE

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Ashutosh Ravikrishnan

Covid-19 and its impact on Singapore's legal community

We are living through history, let's record it

The Covid-19 pandemic has been an unprecedented experience for everyone. Our oral history project seeks to preserve the unique voices and experiences of legal profession living through this historical crisis. Captured in real-time as the pandemic unfurls, these diverse stories from those in legal practice, judiciary, government agencies and law schools will provide researchers with important data to study the effects that COVID has had on the legal community. These interviews will be available on the NAS Portal soon.

- Aedit ABDULLAH

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Ashutosh Ravikrishnan - Simon CHESTERMAN

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Ashutosh Ravikrishnan - GOH Yihan

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Ashutosh Ravikrishnan - Derek HO

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Richard Bautista - Sundaresh MENON

Interviewed by Thian Yee Sze and Foo Kim Leng

- Juthika RAMANATHAN

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Ashutosh Ravikrishnan - Christopher TAN

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Ashutosh Ravikrishnan - Gregory VIJAYENDRAN

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Ashutosh Ravikrishnan - Anthony WEE

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Ashutosh Ravikrishnan - Stefanie YUEN-THIO

Interviewed by Foo Kim Leng and Ashutosh Ravikrishnan

Our oral history programme focuses on two major themes:

Heritage Articles

10 OLY Moments To Remember

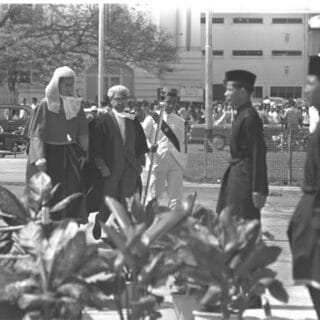

The Opening of Legal Year (OLY) is a ceremony steeped in tradition. And as this list shows, the speeches made there can have a big impact on the everyday practice of law.

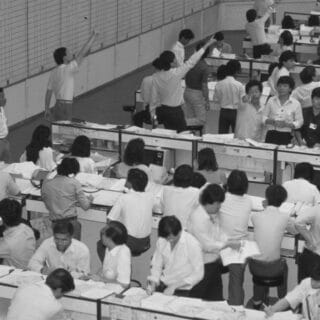

Remembering The Pan-Electric Crisis, Nearly 40 Years On

Why this incident marked a turning point in the evolution of our stock market.

The Toa Payoh Ritual Murders: A Case Of Insanity Or Was It Just A “Wayang”? (Part 2)

The first part of this article took you into the court room where the battle was fought between the defence and prosecution as to whether the murderers were of sound mind. The psychiatric defence failed but could there have been a different outcome?

The Toa Payoh Ritual Murders: A Case Of Insanity Or Was It Just A “Wayang”? (Part 1)

Much has been written about one of Singapore’s most sensational crimes which took place 40 years ago. Delving into unpublished oral history accounts collected under SAL’s legal Heritage Programme and the National Archives of Singapore, we revisit the trial which continues to intrigue long after the case was closed.

The Slips Of Paper That Kept A Profession On Track

Analogue methods of legal research hold a certain nostalgia for Ms Umayal Balakrishnan, who has worked as a librarian at Drew & Napier since 1994.

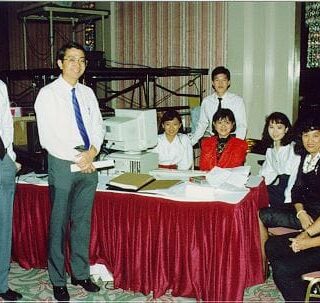

The Long Road To Lawnet, As Told By Charles Lim

It’s difficult to imagine a law firm operating without a computer today. But up until the 1980s, this ubiquitous technology was not something in every law office let alone on every practitioner’s desk. Mr Charles Lim of the Attorney-General’s Chambers shares how officers like himself helped build the landscape we know today.

A Class Act: From Chalk To Transparencies

In the second of a two-part series on the history of the law faculty as told through oral history interviews, Professor Tan Sook Yee recalls her time at the university as lecturer and administrator.

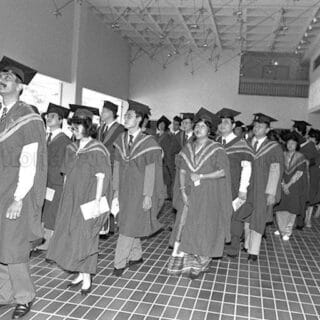

A Class Act: How Singapore’s First Law Faculty Came To Be

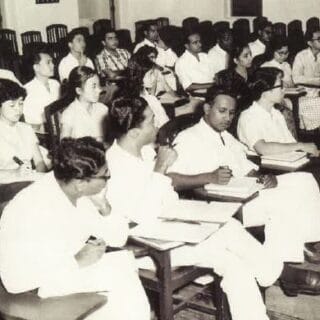

Students across the country have begun the academic year in earnest. SAL marks the occasion with a look at the history of Singapore’s law faculty which took root at the then-University of Malaya. It started in 1959 with barely three academic staff: Dean Professor LA Sheridan, Mr B L Chua and Mr Tan Boon Teik, a magistrate who taught part-time. Mr Tan Boon Teik, who would later become Singapore’s longest serving Attorney-General, continued to teach part-time at the faculty for many years. His wife, Professor Tan Sook Yee, would became the faculty’s 10th Dean in 1980. This two-part series is based on SAL's oral history interviews with former deans Prof Sheridan and Prof Tan Sook Yee. They recount the nascent years of the law faculty and their love of teaching which have nurtured many legal illuminaries who have made their mark in Singapore and overseas.

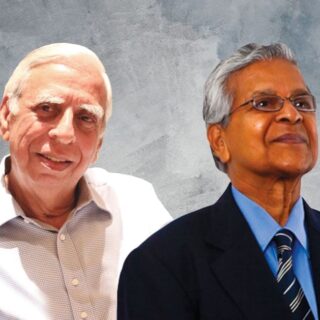

Veteran Trials

These days, we are constantly reminded of the need for resilience and fortitude in the face of Covid-19. For veteran lawyers Mr TPB Menon and Mr Sat Pal Khattar, it did not take a global pandemic to turn their lives upside down. At an age when most of their peers were focused on their studies, they had to shoulder the added responsibility of being head of their households while grappling with the demands of law school. Their stories, taken from excerpts of their oral history interviews with SAL, are inspirational in these difficult times.

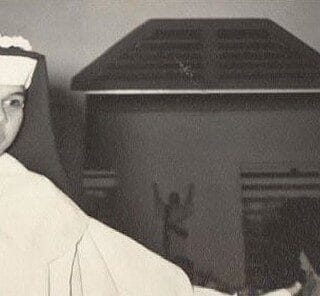

Hold My Hand Till the End: An Interview with Sister Gerard Fernandez

After the trials have ended and the death sentence passed, what happens to prisoners on death row? In an oral history interview, Sister Gerard Fernandez sheds light on the final days of some of Singapore’s most famous death row inmates.

Publications

Making legal history a living subject

For many years, in university courses all over the world, legal history has, at best been a marginal subject, an oddity to be tolerated rather than encouraged.

Dr Kevin Y L Tan

Editor of Essays in Singapore Legal History

One of our earliest projects in documenting Singapore’s legal history was a publication of 10 essays written by a select group of judges, legal practitioners and law academics. Published in 2004, Essays in Singapore Legal History aimed to not only bring the fascinating world of legal history to a wider audience but also serve as a springboard for future study and research. The Academy’s publishing arm now has a Heritage Series which focuses on titles on various aspects of our legal history.

Sample of our books

Legal Tenor: Voices from Singapore’s Legal History (1930 – 1959) is the first of its kind in Singapore. It features audio recordings of 15 of Singapore’s earliest lawyers including David Marshall, Wee Chong Jin, J B Jeyeretnam, Joseph Grimberg, Howard Cashin and former judges, Choor Singh, F A Chua and Abdul Wahab Ghows as they recollected their lives and experiences in the practice of law in the decades leading up to self-governance in 1959.

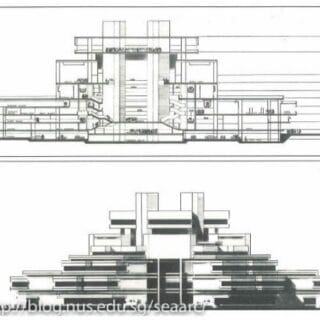

Legal Legacies: The Storeys of Singapore Law aims to tell a brief history of these buildings through the use of photos, architectural drawings and stories told by people who remember what it was like to work or be in these places. Come explore the interiors of the “hush-hush” house and dwellings of some of the most prominent practitioners in the early years of Singapore’s history.

Collaborations

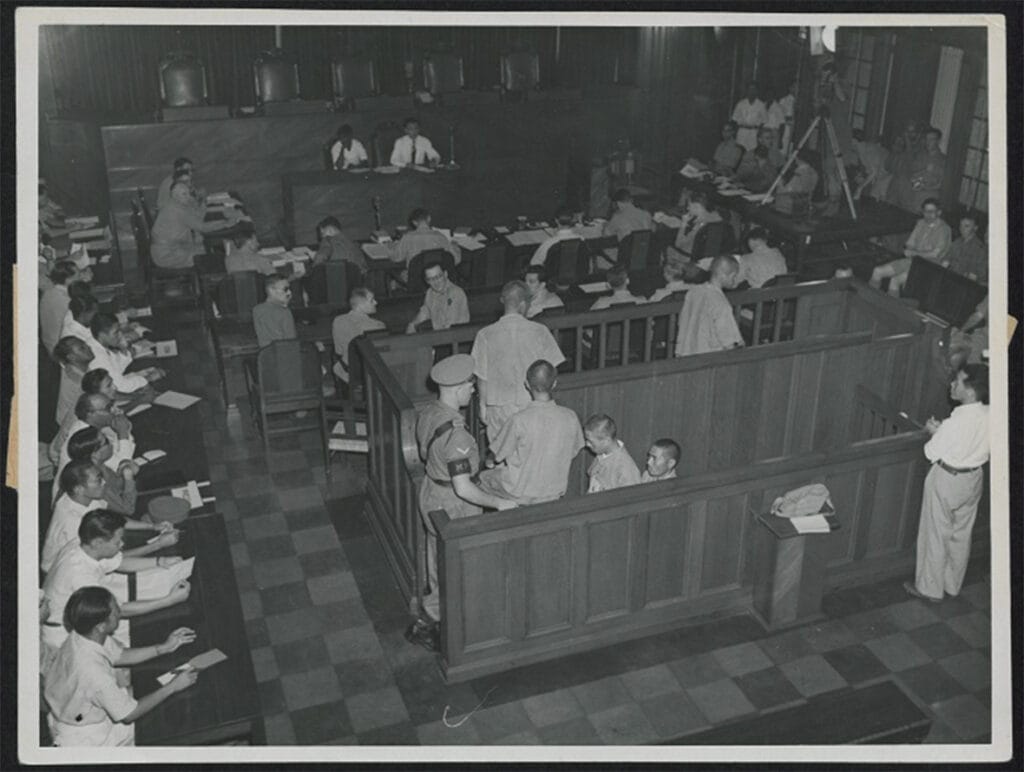

The Second World War irrevocably changed the course of history and the lives of survivors. Its lessons continue to be relevant today.

This project aims to further public understanding on the historic war crimes trials implemented after the war in Singapore. In the 131 war crimes trials held in Singapore over 400 defendants associated with the Japanese military were tried, and hundreds of Asian and Allied witnesses came forward to testify. The Singapore War Crimes Trials Web Portal makes information about these trials accessible to the public. The web portal contains individual case summaries, data on trial participants, and trial background information. It aims to be interactive, user-friendly, and will be updated as research in this area evolves. The portal also points to additional resources for those interested in learning more. Visit the portal here.

The Singapore Academy of Law is proud to support this project coordinated by Dr Cheah Wui Ling and Ms Ng Pei Yi.

Events

Our legal heritage programmes are not just for members of the legal community; we also welcome members of the public and students to explore our rich legal heritage. Follow us on LinkedIn or subscribe to our mailing list to be the first to hear of upcoming heritage programmes.

Open to students from Singapore’s three law schools, Jus Debate can be a two or three-cornered fight with teams battling for victory using costumes, props, characterisation and whatever they can muster to win over the judges with wit, humour and of course historical authenticity in their arguments.

Our legal heritage exhibitions (there have been three so far) have attracted keen interest from members of the legal fraternity and the public.

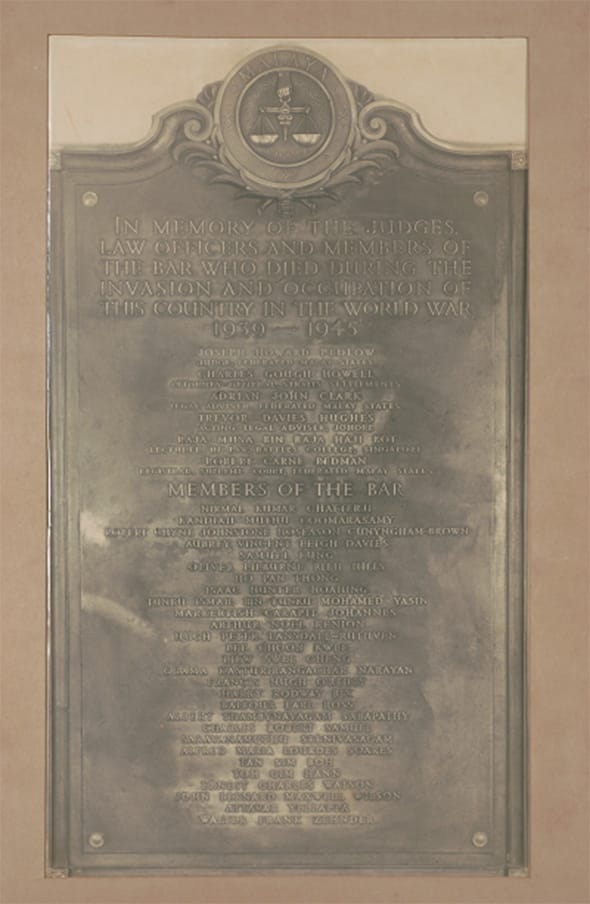

Legal Heritage Exhibition, 1995

One of the artefacts displayed was this memorial plaque which pays tribute to members of Singapore’s legal profession who died during World War II.

Found in the vaults of the Supreme Court, the old flare gun is undoubtedly a relic of our colonial past. Believed to be used in moments of emergency to signal distress, the flare gun has presumably seen the Supreme Court through many incidents of civil unrest.

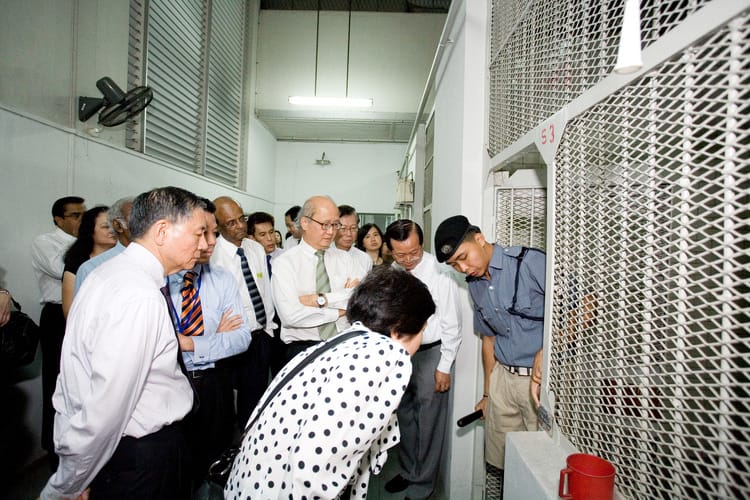

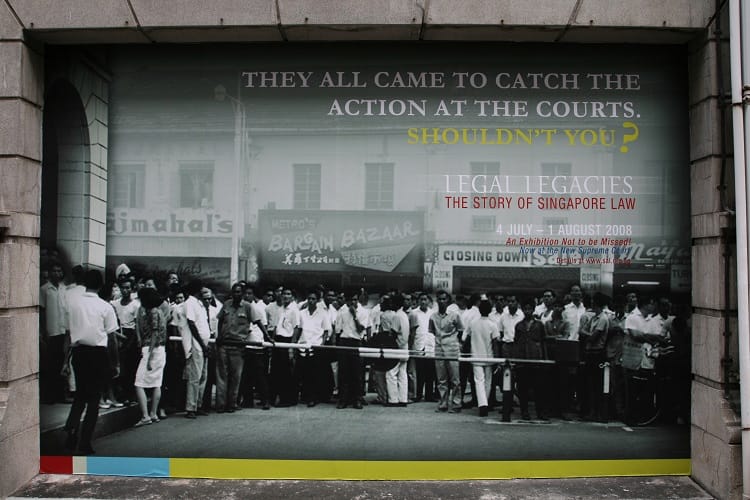

Legal Legacies, 2008

Held as part of the Academy’s 20th anniversary, the exhibition included a tour to the old Supreme Court before it was converted into the National Gallery. View a selection of the Legal Legacies exhibition here and let docents take you on a tour into the old Supreme Court.

#Law & Community, 2013

This one-week exhibition held as part of the Academy’s 25th anniversary focused on two major areas of law that touch the common man: Criminal Justice and Family Law. Besides interesting facts, photos, videos and artefacts, visitors could walk through a prison cell and try their hand on interactive displays.

Wedding photo of Mr Lim Kim San and his wife Pang Gek Kim. Mr Lim was a member of Singapore’s first Cabinet and helmed many key ministries including the Ministry of National Development. The couple’s wedding certificate was one of the rare documents on display at this exhibition. Prior to the Women’s Charter, there was no provision for registration of marriages. Marriages were recognised as valid as long as the necessary customary rites were performed. The use of wedding certificates was a European practice that was adopted by the communities here, in particular by the wealthy Chinese and Peranakan families whose children had been given an English education.

This series of talks and panel discussions on a topic or event from our legal history is one of our most popular outreach programmes.

Our panel speakers include academics, historians, lawyers and judges and they share information on the event from the historical perspective and lessons which we can take from it. These lively sessions which include video presentations are always fully subscribed.

Audience participation is key at our Legal Chronicle events. They are encouraged to share their stories, ask questions, listen to audio recordings from first-person accounts of the incidents and learn more about our legal heritage work over light refreshments.