Writing About Family Law for Those Who Practise It

Are bird’s nest, snow jelly and cordyceps necessities which a parent should pay child maintenance for, or luxuries, which he need not? How about overseas vacations and birthday gifts? While maintenance is by no means a new concept in family law, it remains an area with many interesting aspects for practitioners to navigate, such as this question on what is a necessity versus a luxury for child maintenance purposes.¹

Delving into such issues is part of the work of the three editors of SAL Practitioner’s Family and Personal Law subject area. Over the past year, the journal has published everything from case commentaries, to articles on proving adultery, ethics, and Syariah Law. One area that has been covered in a number of articles in the past year is maintenance—nominal maintenance, child maintenance, and the workings of the new Maintenance Enforcement Office under the Ministry of Law.

Ms Lim Hui Min herself recently co-authored an article on how the courts likely make the distinction between a reasonable expense and luxury. “We thought it would be useful to collect cases where the courts have opined on this issue and try and make sense of what the different judges have said,” explains Hui Min, who has been an editor since April 2024 and also serves as Director of the Legal Aid Bureau (LAB).

“Interestingly, although we got insights into what were luxuries versus necessities, and this was pretty consistent, none of the judgments really define why something is a luxury and why something is not! So we put our own theory on this into the article.”

Putting pen to paper is a useful way of making sense of different concepts, add editors Ms Shahrinah Abdol Salam and Ms Tricia Ho. Being invited to contribute to the journal is an opportunity to pause and interrogate what is often treated as routine. “Once in a while,” reflects Shahrinah, a Deputy Director at LAB, “it helps us to crystallise the points that we learn in our daily work and put it down in writing.”

That resonates with Tricia, a Lecturer at the Singapore University of Social Sciences. She notes that much professional knowledge is passed on informally and through experience. “In class, you can draw on litigation and practical experience, but it is often anecdotal. Publishing allows that experience to be consolidated into a form of knowledge-sharing that practitioners can return to,” she says.

A New Frontier

One area that the editors hope to spend more time on is therapeutic justice. It has emerged as a key frontier in family law, and the editors hope for articles on this which focus more on practice, rather than theory. “We should have a collection of examples of therapeutic justice in practice to show people, ‘Ah, this is how you should do it,'” says Hui Min.

She recalls a case in which the husband’s counsel candidly informed the court that the amount of the outstanding mortgage loan and a term loan taken out on the matrimonial property was lower than the amount agreed between the parties in their Joint Summary.² The judge expressly commended the husband and his counsel for making full and frank disclosure. Raising awareness of such cases where parties have behaved in accordance with the principles of therapeutic justice would be useful to encourage the practice of therapeutic justice, she adds.

It’s a topic close to the heart of the editors—Tricia is currently pursuing doctoral research involving empirical legal research on therapeutic justice in practice. Shahrinah, a former Registrar of the Syariah Court who is now a family law practitioner, observes that many underpinning theories of therapeutic justice in civil family law have long been present within Syariah law.

As Shahrinah explains, features such as the no-fault nature of divorce, processes like hakam³ that emphasise reconciliation, and concepts such as ihsan⁴ are inherently therapeutic. She also highlighted the role of language in Syariah judgments, “It’s quite common to have the Syariah court judges say, ‘After this divorce, parties, please remember your duties to God and to your children.’” For Shahrinah, this is therapeutic justice in practice, “I want to see more of this, because when you say these words to the parties, they tone down. [It’s a] reminder to refocus, redirect on something that’s bigger than just you.”

Why Contributions Matter

For Tricia, contributions to the journal matter because of who it reaches. “We’re doing something useful for the development of family law in Singapore… this article can make a potential impact on the ground because of who reads the journal.” Because SAL Practitioner’s family chapter is read mainly by lawyers in Singapore, it offers a direct line between writing and practice.

Shahrinah points to the value of writing in areas that are often treated as routine. “Because it’s so niche,” she notes, “most practitioners just do it the usual way—this is how it’s always been done.” Writing creates space to examine those assumptions more closely. “You need to take time out deliberately to uncover those depths,” she says, adding that SAL Practitioner provides “a good platform” to explore issues that “have been raised but not really thought about.”

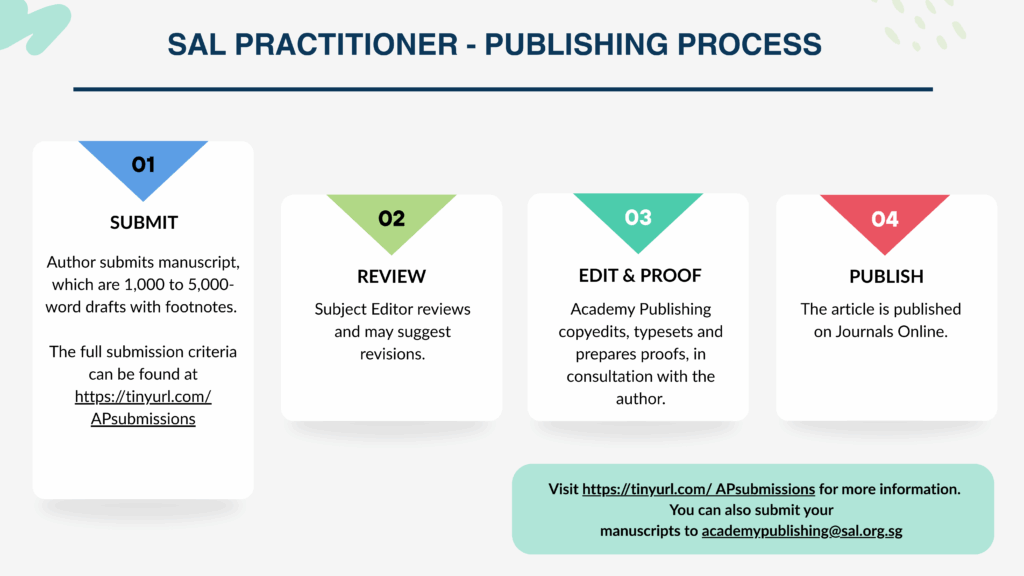

For Hui Min, the process need not be daunting: no polished draft is needed at the outset. “Potential contributors can actually email us saying, ‘This is my idea for this article or case note. These are the three key points I want to make, and this is the time I can deliver it by”. Early conversations with the editorial team will help scope pieces realistically and ensure they remain manageable alongside practice.

Contributions should not be theoretical and need not be groundbreaking. Practitioners who may not otherwise think of themselves as writers may have valuable contributions on unresolved questions they encounter in their daily work, as they are often best placed to identify gaps, ambiguities and areas for improvement and legislative reform. An example is the question of whether the parent of an adult child can claim maintenance for him in the divorce proceedings.

One High Court case said that this should be possible. After reading this case, Hui Min was inspired to write an article on the relevant case law which conflicted with this case, and to examine the policy reasons why this position might actually be better for families.

Encouraging practitioners to think beyond just the case they are doing, Hui Min says: “If you come across an issue in your family or Syariah practice which puzzles you, bothers you, or intrigues you, and found that there isn’t much research on it, that’s exactly the sort of topic we’d encourage you to write on.”

¹ This question was explored in this article “Child Maintenance: Distinguishing Between “Reasonable Expenses” and “Luxuries” [2025] SAL Prac 31.

² XNM v XNN [2025] SGHCF 42

³ Hakam refers to the process of marital conciliation. The Syariah Court Singapore maintains a Panel of Hakam (Marital Conciliators) to facilitate reconciliation if possible, or an amicable divorce if reconciliation is not possible.

⁴ Ihsan refers to the Islamic principle of doing good to others, which is embedded within the Syariah Court divorce processes.

⁵ The case is XFD v XFE [2024] SGHCF 43, and the article is “Adult Child Maintenance in Divorce Proceedings – Who Should Apply?” – XFD v XFE [2024] SGHCF 43